|

________

Last Game

Tribe- 11 Yanks - 1

Next Game:

Indians @ Yanks

________

Home

Galleries

1999 Division Series

1999 ALCS

1999 World Series

1998 World Series

Yankee Perfect Games

Donnie Baseball

Joe DiMaggio

SI Yankee

Covers

Yankee Web-Rings &

Links

BOSOX Tribute

________

| |

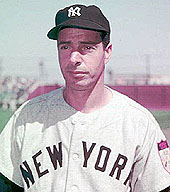

Joe

DiMaggio

1914 -

1999

Joe D

Photo Gallery

(The following are articles that

I enjoyed reading. Each article lists the author as they were not written by

me-obviously)

DiMaggio an American hero

By Bob Kimball, USATODAY.com

American icon Joe DiMaggio, who patrolled center field with grace and precision and won

pennant after pennant with the New York Yankees, died Monday at his home in Hollywood,

Fla.. The Yankee Clipper was 84 and had undergone surgery for lung cancer in October

before developing pneumonia. DiMaggio's impact on the Yankees, sports and American culture

was dramatic following his arrival in New York from San Francisco in 1936.

The Hall of Famer starred on four World Series winners in his first four major league

seasons and wound up leading the Yankees to 10 American League titles and nine Series

championships in 13 years. DiMaggio was, in short, one of the great winners in history who

also surrendered three years in the middle of his playing career to military service. Fans

might have hated the Yankees, but they always admired and even rooted for DiMaggio.

After baseball retirement in 1951, he made headlines by marrying - and divorcing - movie

queen Marilyn Monroe, appearing on TV as Mr. Coffee and generally being Joe DiMaggio. It

was during his brief marriage to Monroe in 1954 that he supposedly made one of the great

rejoinders. Upon returning from entertaining troops in Korea, Monroe told her new husband,

"Darling, you've never heard such cheering." Replied the often understated

DiMaggio, "Yes I have."

DiMaggio stands with game's

giants

By Tom Weir, USA TODAY

To some, he was Mr. Coffee. To others, he was the man who for decades regularly sent red

roses to the grave of his second wife, Marilyn Monroe. There also were those who knew him

only because of a musical question, "Where have you gone, Joe DiMaggio?"

But baseball fans knew him long before any of that. And, for them, today there is a sad

truth provided by the second part of the Simon and Garfunkel lyric:

"Joltin' Joe has left and gone away."

DiMaggio, 84, died shortly after midnight

Monday at his home in Hollywood, Fla., surrounded by friends and family members. The exact

cause of death was not known, but he had suffered from lung cancer and other ailments.

Funeral arrangements have not been disclosed. He is survived by his brother Dominick, son

Joe Jr., grandchildren Paula and Cathy, and four great-grandchildren.

The son of an immigrant crab fisherman,

DiMaggio was one of nine children in a family that also sent brothers Dom and Vince to the

major leagues. He was born Giuseppe Paolo DiMaggio in 1914 in the San Francisco-area town

of Martinez, but came to be known as the Yankee Clipper while in effect manning the helm

of baseball's best team for 13 seasons.

In the chain of New York Yankees dynasties that ruled baseball from the '20s to the '60s,

DiMaggio was the solid-gold link between the eras of Lou Gehrig and Mickey Mantle. The

first of DiMaggio's three MVP seasons, 1939, was the year Gehrig took the field only eight

times and ended his streak of 2,130 games played. DiMaggio's last season, 1951, was

Mantle's rookie year.

DiMaggio's seemingly effortless grace in center field and at the plate has inspired

countless odes. Les Brown and his Band of Renown dedicated a song to DiMaggio in the '40s,

and even Nobel Prize-winning author Ernest Hemingway devoted several passages of dialogue

to DiMaggio in The Old Man and the Sea.

When at last the old man has landed his catch, he muses, "I wonder how the great

DiMaggio would have liked the way I hit him in the brain?"

But perhaps Yankees manager Casey Stengel best captured the ease of DiMaggio's greatness:

"Joe did everything so naturally that half the time he gave the impression he wasn't

trying," Stengel once said. "He made the rest of them look like plumbers."

The streak

In 10 of DiMaggio's 13 seasons, the Yankees reached the World Series, and in nine they

were crowned Series champs. DiMaggio still ranks as the only player to win a World Series

ring in his first four seasons (1936-39), but his baseball immortality will be marked by a

record that most of the game's experts agree will accompany him to the grave.

After slumping early in the 1941 season, DiMaggio eked out a scratch single during a

1-for-4 performance May 15. He didn't go hitless again until July 17, a stupefying string

of 56 games.

Six games of the streak pitted DiMaggio against starting pitchers who, like himself, were

headed for the Hall of Fame: Bob Feller (twice), Hal Newhouser (twice), Lefty Grove and

Ted Lyons.

Ending the streak required a pair of fielding gems by Cleveland third baseman Ken Keltner,

but even then DiMaggio wasn't really done. The next game, he began a 17-game hitting

streak.

DiMaggio had prepped for that historic run as a teen-ager. He had left high school after

just one year to work in a fish cannery, then signed to play with the San Francisco Seals

of the Pacific Coast League. At 18, DiMaggio had a 61-game hitting streak for the Seals,

which still ranks as the longest in all of professional baseball.

That 1933 streak made him one of the most publicized prospects in baseball history, but a

knee injury the next year cooled the interest of all teams except the Yankees. They bought

his contract for $25,000 and accepted the Seals' condition that DiMaggio would play one

more minor league season in San Francisco before donning pinstripes. In that season,

DiMaggio batted .398.

Cheers and jeers

DiMaggio's Yankee Stadium debut May 3 attracted an estimated 25,000 Italian-Americans who

showed up to wave their homeland's flag. In recent years, he naturally had received huge

ovations while throwing out ceremonial first pitches at postseason games. And the cheers

he received during pre-fight introductions of celebrities at major boxing events were

always second only to those for Muhammad Ali.

But, contrary to modern impressions, the applause wasn't always so unanimous for the man

who earned baseball's first $100,000 salary.

After driving in 167 runs in 1937, DiMaggio demanded a $45,000 contract in 1938. He had to

settle for a reported $25,000, but by the time his holdout ended he had been vilified by

the press and inundated with hate mail. The next year, an infamous article appeared in

Life that was littered with anti-Italian slurs against DiMaggio.

In 1942, another contract dispute led to a questioning of DiMaggio's patriotism. The

Yankees, anticipating financial downturns because of World War II, asked DiMaggio to take

a pay cut. When DiMaggio refused, Yankees management turned the holdout into a

red-white-and-blue issue.

That season, DiMaggio was roundly booed in American League stadiums. The next year, he

enlisted in the Army and, at the age of 28, lost three potentially prime seasons to

military service.

Along with a career-long succession of injuries, those wartime years ended any shot for

DiMaggio to rank among the top 10 or top 20 in any of the major statistical categories.

He also was deprived of an excellent chance to join the ranks of .400 hitters. Batting

.412 in early September 1939, DiMaggio developed an eye problem and finished at .381,

still good enough to win one of his two batting titles.

But DiMaggio does deserve to be remembered for the virtually unmatched efficiency of

producing 361 career home runs while striking out only 369 times. While hitting 714

homers, Babe Ruth fanned 1,330 times. For Mantle, the ratio was 536-1,710. For Reggie

Jackson, 563-2,597.

Comfort of silence

The one time DiMaggio did strike out quickly was in his 1954 marriage to Marilyn Monroe,

which lasted only nine months.

Most famous quote from the marriage came when Monroe returned from entertaining 100,000

U.S. troops in South Korea. She told her husband, "It was so wonderful, Joe, you

never heard such cheering."

"Yes, I have," was the reply of the man who played in 51 World Series games.

In their divorce proceedings, the sex symbol of the '50s said that the sports icon of the

'40s often wouldn't talk to her, a complaint that's easy to believe considering the way

DiMaggio adamantly guarded his privacy after retiring from baseball.

He maintained a high public profile as a corporate spokesman, including TV ads for Mr.

Coffee brewing machines. DiMaggio also served as a hitting instructor for the Oakland A's

and Yankees but never gave in-depth interviews, even though major book publishers had

lucrative, standing offers for a tell-all book.

But that wasn't DiMaggio's style, whose manner is perhaps best captured by the way he

retired in December 1951, after what was only his second sub-.300 season. The Yankees were

reported to have offered him $100,000 for another season, even if he had to severely limit

his playing time.

Asked how he could turn down such an offer, DiMaggio said simply, "I no longer have

it."

The story then was the same as it is now.

Joltin' Joe has left and gone away.

Quotes on the death of Joe

DiMaggio

By The Associated Press

Comments from the fans and others on the death of Joe DiMaggio:

''He was a classy individual. ... When he finished playing, he had a very special aura. He

had a lot of dignity about him besides being an excellent ballplayer.'' - Howard Fine, a

plastics manufacturer from Mamaroneck, N.Y.

''He was what baseball was all about before we got to that high-priced stuff.'' - George

Ladino, a Boston native now living in London who was traveling through New York's Grand

Central Terminal.

''It's the passing of a person from a time when baseball was the way it should be, when

there was a higher ethical and moral standard.'' - Doug Connor, a financial industry

worker from Irvington, N.Y.

''Joe DiMaggio was one man who truly epitomized the 'Hemingway Hero.' He confronted

adversity with grace under pressure.'' - Joe Dorinson, author of ''Jackie Robinson: Races,

Sports and the American Dream,'' which had a section comparing Robinson and DiMaggio.

''For several generations of baseball fans, Joe was the personification of grace, class

and dignity on the baseball diamond. His persona extended beyond the playing field and

touched all our hearts. In many respects, as an immigrant's son, he represented the hopes

and ideals of our great country.'' - Baseball commissioner Bud Selig.

''Like his many fans across America, and indeed, around the world, the Yankees are deeply

saddened by the passing of Joe DiMaggio, one of our own and one of the greatest of all

time. It was the class and dignity with which he led his life that made him part of all of

us.'' - Yankees owner George M. Steinbrenner.

''He was the kind of guy that exemplified what a major leaguer should be like, and act

like, and play like. ... He played the game with so much intensity. He played the game

with pride. He wore the Yankee uniform with dignity and character.'' - former LA Dodgers

manager Tommy Lasorda, interviewed on CNN.

''Where have you gone Joe DiMaggio? A nation turns its lonely eyes to you.'' - Paul

Simon's lament to lost heroes in ''Mrs. Robinson.''

Facts and figures of Joe

DiMaggio

Nov. 25, 1914: Giuseppe Paolo (Joseph Paul) DiMaggio born to Giuseppe and Rosalie DiMaggio

in Martinez, Calif.

July 5, 1931: At 17, DiMaggio makes his debut with Rossi Olive Oil, a team in the Boys

Club-sponsored McNamara B Winter League, which is an amateur recreation league.

1932: Throughout the summer, he fills in with Sunset Produce, a Division A semipro club,

and the Avalons. Here he gains experience against older and better players. Late in the

season, he joins Baumgartens AA Club in the Recreation League. DiMaggio plays with older

brother Vincent for the last three games of the Pacific Coast League (PCL) season with the

San Francisco Seals.

1933: DiMaggio's career as an outfielder begins when he plays right field in the opening

Seals-Portland game.

May 28, 1933: DiMaggio starts a 61-game hitting streak in the second game of a

doubleheader against first-place Portland. He breaks the league record of 49 set by

Oakland's Jack Ness in 1915.

1934: In May, DiMaggio injures his knee after a family celebration of his streak. In a

game Aug. 10, he reinjures himself and has to sit out the rest of the season.

Nov. 23, 1934: The New York Yankees offer Seals owner Charlie Graham $25,000 and five

players for DiMaggio. The deal is mutually beneficial: DiMaggio plays with the Seals for

the 1935 season, Graham gets his five players and the Yankees take DiMaggio for '36 -- if

his knee holds up.

1935: DiMaggio is voted PCL Most Valuable Player. Abe Kemp of the San Francisco Examiner

writes, "Just a word about Joe DiMaggio, who has finally convinced me that he is the

greatest ballplayer I have ever seen graduate from the Pacific Coast League."

1936: DiMaggio begins his 13-year run with the Yankees. His brother Tom negotiates an

$8,500 contract, the highest salary New York ever offered a rookie. At the home opener,

DiMaggio plays left field and bats third in the lineup, Babe Ruth's old spot. Later in the

season, DiMaggio moves to Ruth's right-field position. By August, he moves again to center

field.

1937: DiMaggio re-signs for double his rookie salary -- $17,000 a year. But the Yankees

recoup some of the money: They add seats in the right-field stands to accommodate fans now

attending games to see him.

July 5, 1937: The Yankees are tied 4-4 with Boston; the bases are loaded. DiMaggio hits it

long to left field. The ball lands in the bullpen. This is his first grand slam in the

major leagues. DiMaggio is voted player of the year by the Yankees and Baseball Magazine.

He collected the most votes for The Sporting News all-star team. This is the year DiMaggio

earned the nickname "Yankee Clipper." (Radio broadcaster Arch McDonald gives

DiMaggio the moniker because of the way he "appeared to glide across the outfield in

pursuit of fly balls.")

1939: DiMaggio earns his first batting title with a career-high .381. He makes what is

believed to be the best catch of his career -- a Hank Greenberg drive to the monuments in

left-center, behind the flagpole and in front of the 461-foot sign. DiMaggio ran about 200

feet to get to the ball.

Nov. 19, 1939: DiMaggio, 24, marries actress Dorothy Arnold, 21, at St. Peter and Paul

Cathedral in San Francisco.

1940: DiMaggio earns his second batting title with a .352 average. He also has 31 home

runs and 133 RBI in 132 games.

May 15, 1941: The Yankees play the Chicago White Sox at home and DiMaggio singles in one

of his four at-bats. He hits in the next 55 games. It is still a record. He hits .357 for

the season and is named MVP.

Oct. 23, 1941: DiMaggio's only child, Joseph Paul DiMaggio Jr., is born.

1942: DiMaggio has 186 hits and bats .305 in 154 games. On Dec. 3 he enlists in the Army

Air Forces.

1943: DiMaggio, a staff sergeant, is a center fielder for the 7th Air Force team. (In

1944, it would play a Navy team that includes Johnny Mize at first and Pee Wee Reese at

shortstop.)

Oct. 11, 1943: Dorothy DiMaggio files for divorce.

Sept. 14, 1945: DiMaggio is discharged.

1947: DiMaggio begins the year with surgery to remove a 3-inch bone spur from his left

heel. He ends it as MVP, batting .343 and making one error in 141 games.

1948: DiMaggio leads the league with 39 home runs and 155 RBI despite recurring pain from

a bone spur. He hits his 300th career home run this season.

1949: On Feb. 7, DiMaggio becomes the first $100,000 ballplayer. He earns his money this

season. Playing hurt (now his right heel) and exhausted (from a viral infection), DiMaggio

pulls himself out of the pennant-deciding game with the Boston Red Sox. The Yankees win

5-3 and go on to their 12th World Series title. He hits .346 for the season. His father,

Guiseppe, dies in May.

1950: DiMaggio plays in his ninth World Series in 12 years. His mother Rosalie, 72, dies.

1951: The Yankees play in -- and win -- another World Series. It would be DiMaggio's last.

On Dec. 11, he announces his retirement: "When baseball is no longer fun, it's no

longer a game. And so, I've played my last game." The legacy of his 13-year career:

2,214 hits, .325 batting average, 361 home runs and 1,537 RBI. He is arguably the most

elegant man to wear Yankees pinstripes.

1952: DiMaggio's number (5) is retired.

Jan. 14, 1954: DiMaggio weds actress Marilyn Monroe. The marriage lasts less than a year

(to Oct. 27) but the affection endures. After Monroe's death Aug. 5, 1962, DiMaggio

arranges the funeral. He never remarries and leaves roses at her grave weekly for 20

years.

1955: DiMaggio is inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. He played on 10 pennant winners

and nine World Series champions in his career. He was an All-Star in all 13 years.

1967: DiMaggio begins a two-year stint as coach and consultant with the Oakland Athletics.

1969: In a nationwide poll, DiMaggio is voted baseball's greatest living player.

1972: DiMaggio becomes a spokesman for Mr. Coffee. He also made commercials for the

coffeemaker company in '74 and '84.

March 8, 1999: DiMaggio dies after a lengthy illness.

Quote: ''I want to thank the good Lord for making me a Yankee.'' - from remarks on Joe

DiMaggio Day at Yankee Stadium, Oct. 1, 1949.

Sources: USA TODAY research; wire reports; Dick Johnson and Glenn Stout, DiMaggio: An

Illustrated Life; Baseball Weekly

Compiled by Joan Murphy and Tammi Wark, USA TODAY

An appointment Joe D

couldn't make

By The Associated Press

Joe DiMaggio fell a month and a day short of another appearance at Yankee Stadium.

DiMaggio, who died Monday, had tacked to his bed a sign that said ''April 9,'' opening day

at Yankee Stadium, where he was supposed to throw out the first ball.

''Five days ago, on March 2, I visited with Joe at his home in Hollywood, Fla. He was weak

but spirited and alert,'' said George Steinbrenner, the New York Yankees' owner. ''I told

him, 'Joe, you have a date with the Yankees on opening day. We are counting on you to

throw out the first ball.'

''He just smiled.''

DiMaggio made a lot of people smile, as was apparent by the tributes that began pouring in

minutes after his death was announced.

He also transcended baseball, much like Michael Jordan in basketball a half-century later,

and was a spokesman long after he retired for a variety of products, including Mr. Coffee.

In New York's Grand Central Station, a bank he endorsed simply posted the pinstriped

number ''5.''

And he reached fans and non-fans as an American hero.

''Even though I was never one of those people who cared about baseball, I care a lot about

Joe DiMaggio,'' said former New York Mayor Ed Koch, who grew up in the city during

DiMaggio's heyday.

''He represented the best in America. It was his character, his generosity, his

sensitivity. He was someone who set a standard every father would want his children to

follow.''

People in the sport agreed.

''His persona extended beyond the playing field and touched all our hearts,'' baseball

commissioner Bud Selig said. ''In many respects, as an immigrant's son, he represented the

hopes and ideals of our great country.

''I idolized him from afar as a child growing up in Milwaukee. In later years, when I had

the opportunity to become acquainted with him, my admiration grew. Being with him was an

event, bringing on an air of excitement, anticipation and joy.''

Tommy Lasorda, former Los Angeles Dodgers manager, suggested that DiMaggio's record

56-game hitting streak may stand for another 100 years, unlike Babe Ruth and Roger Maris'

home run records and Lou Gehrig's consecutive-game streak.

''He was always kind of shy,'' Lasorda said of DiMaggio. ''He felt uncomfortable with a

lot of people, but yet he was always there as a tremendous representative of our game of

baseball. He was an icon.''

In Albany, a bill is before the New York legislature to rename the city's West Side

Highway for DiMaggio.

''I'm comforted, as are all New Yorkers, that we informed him before he died that the West

Side Highway will be renamed the Joe DiMaggio Highway,'' said Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, a

longtime Yankees fan.

''As long as baseball is played, Joe DiMaggio will exemplify the very best.''

In Cooperstown, N.Y., the Hall of Fame flag was at half-staff and a wreath was placed on

DiMaggio's plaque.

The Hall has also scheduled special DiMaggio video programming for March, put a tribute on

its Web site and is planning an exhibit.

It will include the glove that outfielder Al Gionfriddo of the Brooklyn Dodgers used when

he robbed DiMaggio of an extra base hit with a spectacular running catch in the 1947 World

Series, and DiMaggio's contract for 1948, the first in sports to reach $100,000. Even the

pen is there.

The man they looked up to

Even to present Yankees, DiMaggio was unapproachable

Associated Press

TAMPA, Fla. — David Cone never asked Joe DiMaggio for his autograph. He was too

afraid, so he went out and bought a dozen from a collector.

"I don't remember what the exact price was, but it was a lot," the New York

Yankees pitcher said Monday, recalling the purchase about a year ago.

"He really lived up to his billing. He was the greatest living player. He just had

such a dignity and an elegance about him that nobody can match in today's game. Even the

greatest players in today's game can't match that elegance that he had. He's one of a

kind."

DiMaggio, who died Monday at his South Florida home, played for 10 pennant winners and

nine World Series champions with the Yankees.

Fans visiting the spring training complex placed flowers in front of a monument for him

outside Legends Field, and the No. 5 was stitched onto the left sleeve of each player's

jersey.

The Yankees ran a 90-second videotape of DiMaggio highlights before observing a moment of

silence before the start of Monday night's game against the Philadelphia Phillies.

"Joe DiMaggio is baseball. He's a national hero," said Sandra De Santis, a

Highland Park, N.J. mother, whose 11-year-old son Gregory placed a bouquet is front of the

plaque that reads:

"From 1936-51, Joe led the Yankees through their most dominating era. His excellence

on the field propelled the Bombers to 10 World Series and his graceful stroke was one of

baseball's greatest pleasures."

By early afternoon, the Yankees posted a security guard to keep TV cameramen and early

arriving fans off the grass in front of the monument, which is part of a tribute to

all-time club greats.

Later, the club placed a huge spray of flowers and a painting of DiMaggio at the site.

"Very few people touched so many generations and so many lives. He had a tremendous

impact on so many people. He was part of the fabric of America," general manager

Brian Cashman said.

DiMaggio's 56-game hitting streak in 1941 is considered one of the greatest records in

sports, and current Yankees marveled about the mystique that set him apart from other Hall

of Famers.

"I met him a few times," Cone said. "He told me that he'd seen me pitch and

sometimes I looked unhittable and sometimes I looked hittable. I didn't know how to take

that. But just the fact he knew who I was was enough for me."

Catcher Joe Girardi talked about what a thrill it was to have his picture taken with

DiMaggio when he threw out the first pitch during a playoff game in 1996. Darryl

Strawberry predicted no one will ever hit safely in 56 straight game again, while Derek

Jeter described DiMaggio as "everything a ballplayer would want to be."

Jeter, noting DiMaggio was an intensely private person, said most players were reluctant

to approach him during his occasional trips to Yankee Stadium.

That, however, didn't mean they didn't soak up as much of the Yankee Clipper as they

could.

"He had more presence than anybody I ever met. When he was around, you knew it.

Everybody lit up. The whole clubhouse would be abuzz when Joe D. walked in," Cone

said.

Longtime baseball executive Arthur Richman, now a senior adviser to the Yankees, recalled

DiMaggio as a friend and one of the fiercest competitors in the game.

"I started watching him in 1936. I always said the greatest player I ever saw was

Babe Ruth. But he was in a class by himself. He was the greatest home run hitter that ever

lived and he was a great pitcher. How many guys would pitch and hit home runs?"

Richman said.

"When it came down to the greatest player, I think about (Stan) Musial, and (Willie)

Mays and (Ted) Williams," he said. "But DiMaggio was the one man, if my life

depended on it, I'd want at the plate to get that base hit in the ninth inning. And he did

so many times."

We will never know his kind

again

The Clipper's mystery built the myth

By Art Spander

FOX Sports Online

NEW YORK — He was a reminder of innocence lost and championships won, of a time when

the country had heroes, not superstars; of an era when modesty was in vogue and privacy

was in style.

He was a celebrity in a pre-celebrity culture.

We didn't know everything about Joe DiMaggio, and that was part of the attraction. We knew

about his records. And his background. And his work ethic.

We knew that he was elegant and diffident, and that he never made an easy catch look

difficult.

But we didn't know what transpired behind closed doors, or sometimes even in front of open

ones, and that was all for the best because it is mystery, as well as mastery, that helped

construct the myth.

In the final line of his final column, the great Red Smith wrote, "I told myself not

to worry; that someday there would be another DiMaggio."

The suggestion was more a remembrance of things past than a forecast of things possible.

There will never be another DiMaggio. Red Smith knew it. We all knew it.

Society has changed, and not necessarily for the better.

Legends do not flourish under the scrutiny of the television camera. The bright lights

display multi-millionaire athletes in Armani being led to and from courthouses by

high-priced lawyers. We're assaulted with stories of player selfishness and owner greed,

bombarded by tell-all books in which players trash their teammates and demand all the

credit for themselves. Even the greatest current icon, Michael Jordan, has not been given

immunity from the harsh glare of the public spotlight.

But to the end, DiMaggio the Legend remained properly enigmatic, tantalizingly private.

There would be no declarative autobiography, no appearances on talk shows. There would be

only silence and the memory of how he played the game.

Baseball owned America in the 1940s and early 1950s, and Joe DiMaggio owned baseball.

Rogers and Hammerstein evoked his name in the lyrics in "South Pacific." Every

boy grew up idolizing "Joltin' Joe." And for good reason.

He came out of the Great Depression and into World War II, symbol of a nation advancing

from one struggle to another, prototype of a time that was glorious in memory if not

exactly in fact.

There was nothing contrived, whether in his play or his nickname, "The Yankee

Clipper." What could be more appropriate, more descriptive? He sailed along through

waters troubled and untroubled.

He rarely showed emotion. "It wouldn't look right," explained DiMaggio.

DiMaggio never told anybody how good he was. His skills spoke volumes. He never got into a

brawl. He had the aspect of a Greek god. Ted Williams, another great player of the time,

said DiMaggio even looked good striking out, not that Joe struck out very often. DiMaggio

was sunlit afternoons on green fields in a time that now seems tinged with gold. We had

never heard of expansion, of free agency, of franchise moves, of night World Series games.

We had never heard of downsizing and disloyalty and terrorist bombings.

"Where have you gone Joe DiMaggio?" asked Paul Simon's lyrics. It was a

metaphorical search for our past, a generational lament. "A nation turns its lonely

eyes to you . . . " Now he is gone, along with our youth.

A fisherman's son who lived the American Dream. He rose above his beginnings. He cared

about his image. In his last season, 1951, he was asked why he didn't coast a bit, take it

easy. "Because," answered DiMaggio, "there may be some kid who never saw me

play before."

Isn't that what it's all about? To go every day and give one's best, to fight the good

fight? That's what DiMaggio did.

He was self-effacing, the embodiment of what a great athlete is supposed to be, a role

model if you will. "I never want to hurt anyone's feelings," he said once.

"And I don't want to be embarrassed."

He rarely was. At least as far as we understood, and that is what counted. He was someone

in who to believe, the embodiment of dignity. Even when persuaded some 50 years ago to do

a book on himself, DiMaggio found it difficult to be egotistical. He titled it,

"Lucky to be a Yankee."

Truth to tell, it was the Yankees who were lucky to have DiMaggio. Along with the rest of

us.

We will never know his kind again.

|